Check Out Minoosh Zomorodinia’s Story at VoyageLA

Today we’d like to introduce you to Minoosh Zomorodinia

Hi Minoosh, we’d love for you to start by introducing yourself.

Art has always been an integral part of my life, helping me overcome various challenges along the way. I grew up in a devout Muslim family in Tehran, Iran, where higher education was not considered an option for girls, though art and craft were encouraged. I attended many art classes before going to college. During high school, the Iran-Iraq war had a profound impact on my life and artistic expression, as there was a scarcity of materials and goods, and much of the art produced was politically charged.

I studied photography at Faculty of Art and Architecture University in Tehran. My twin sister and I were the first women in our family to attend college. Although my favorite genres were documentary and journalism, I didn’t have the courage to pursue them, so I explored various fields of photography instead, from studio and commercial work to architectural, and art for several years.

I worked with the group “Panj-e-Baz” (meaning “Open 5”) while also documenting the work of other artists as an official photographer at various Environmental Art Festivals. I was interested in ephemeral work, art in nature, and collaboratively, we created site-specific installations in various cities across Iran.

In 2009, I moved to the United States where I studied Multimedia Art and Video Art at Berkeley City College. This marked a significant shift for me from photography to filmmaking which continued as I pursued a second master’s degree in New Genres at San Francisco Art Institute. SFAI was a challenging environment; as a Muslim, I frequently experienced marginalization and invisibility. I turned to performance, video, and photography as outlets to explore and confront these challenges through my art.

My interest in the environment and nature led me to connect with the Women Eco Artists Dialog, a Bay Area-based non profit organization, through Patricia Watts, whom I encountered and was a speaker in Andree Singer Thompson’s EcoArt Matters Class at Laney College in 2009. My immigration to the United States profoundly changed me; it deepened my understanding of social justice, exposed me to other cultures, and fostered an openness to diversity. I employ walking as a catalyst to reflect themes of nomadic lifestyles and colonialism. In these art work, I symbolically claim ownership of the land.

I have been fortunate to freelance and document events for many art organizations in the Bay Area since my graduation. Since 2015, I have taught a variety of courses, including EcoArt Matters, Environmental Installations, Multimedia Art, Walking Art and Photography at various institutions such as California College of the Arts, UC Berkeley, San Francisco Art Institute, University of Nevada, San Francisco Comunity College, and Peralta Community Colleges.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

Not at all. For me, being a woman has been the most significant struggle of my life. I struggled with my gender and often wished I were a boy, especially when I saw the freedoms my brothers and male cousins enjoyed. Women of my generation were continually oppressed, expected to prioritize others, and forced to sacrifice their own beliefs and desires to please those around them. Respecting parents and society was always a priority for women. However, over time, I learned to embrace myself. Art, in fact, became a healing force that helped me overcome these feelings.

Being a Muslim presents additional challenges, especially in the art community in Iran and in facing Islamophobia in the U.S. I push myself to engage with other communities to make a difference. Much of my work addresses these struggles, conflicts and for some time now, I have expressed these feelings through video, photography, and performance. I use my body in my work, which presents another challenge, but I do it to create change and embrace vulnerability. I try to Navigate the art world without falling into stereotypes and clichés, which can be difficult.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

I use art as a tool to tell stories and reflect on everyday experiences. I believe in the concept “Art is Life,” a term introduced by conceptual artist Joseph Beuys. I always aspired to be an environmental artist, minimizing my impact on the environment by upcycling and recycling my materials and works. I create installations, projected videos, and projection mapped onto various surfaces and sculptures to establish a third space that engages audiences.

My primary focus is on time and space, and I use my body as a tool to record and document them through walking. This performative act results in artifacts that capture the essence of my journey. I am committed to challenging myself to use different technologies to transform my performances into tangible objects. I aim to create participatory performances that foster community and connect with diverse cultures.

I don’t consider myself different from others, but what sets me apart is my resilience. I use my failures as opportunities to grow, learn, and connect with others. I hope to make a difference through teaching, creating art, and being an active part of the community.

What makes you happy?

Spending time in nature and feeling connected to the environment grounds me; it reminds me of the intricate balance of life and the beauty of simplicity. Nature fuels my passion for art and helps me heal and recover from struggles. It inspires me to create and drives my desire to express this deep bond. Through my art, I hope to share this connection with others in order to inspire them to appreciate and respect the natural world. It’s a shared space for all living beings where we can learn to respect and honor the interconnectedness of life.

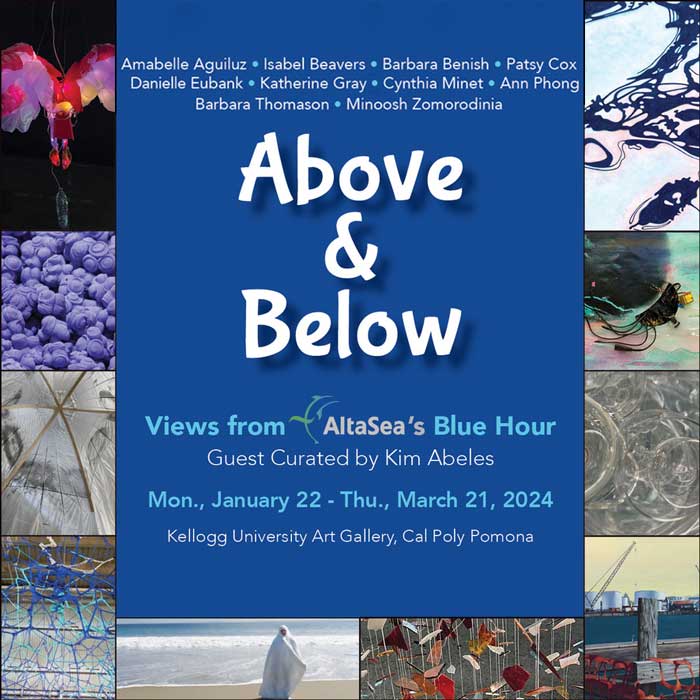

Above and Below: Views from AltaSea’s Blue Hour” at the Kellogg University Art Gallery, Cal Poly Pomona. Art from the original venue at the AltaSea-Port of Los Angeles will be on view at the Kellogg along with documents representing all the art and events. Abeles is Guest Curator In collaboration with Michele Cairella Fillmore, Curator of the Kellogg University Art Gallery.

Participating Artists:

Amabelle Aguiluz, Isabel Beavers, Barbara Benish, Patsy Cox, Danielle Eubank, Katherine Gray, Cynthia Minet, Ann Phong, Barbara Thomason, and Minoosh Zomorodinia

Artists’ Reception Sat., Feb. 3 | 2-5pm

Campus Reception Tue., Mar. 5 | 4- 6pm

Exhibition runs from January 22 – March 21, 2024

AltaSea at the Port of Los Angeles is an ocean research and innovation institute which broke ground in 2017 at the historic warehouse berths. The volunteers and staff educate through art and science about our relationship to the ocean and its importance to the health and future of the planet. The exhibition at the Kellogg Gallery offers a beautiful view of artworks from the original venue and pays homage to the leadership of women at the forefront of art and science in service to the planet.

Review: Transcending Physicality @ SF Arts Commission Gallery by Nanette Wydle published, Slippage

We live in a time of contested landscape. Locally and globally we have disagreement regarding the state of our environment, the factualities of climate change, and who has rights to be somewhere, anywhere. Yet, many of us are ingrained with strong connections to specific locations—the places we inhabit, remember, and revere. Whether one believes in science or not, places are, in large part, the defining sources of many aspects of our collective and individual identities. The flora, fauna, climate, and experience of place are imprinted in our diverse and various cultures.

Transcending Physicality: The Essence of Place at San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery is an exhibition of 14 international artists curated by Minoosh Zomorodinia. The exhibition communicates perspectives about human engagement with natural and built environments, and crises of these via works charged with subliminal agendas and cool intellectualism regarding the (oftentimes harsh) realities of our relationships with the land.

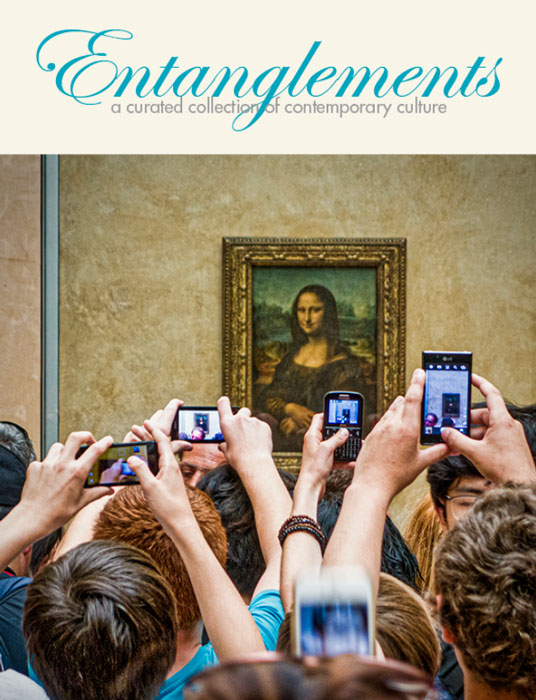

Entanglements

a curated collection of contemporary culture

Entanglements is a printed book available through Hunger Button Books, October 2022

Interview with Whirligig

ecoartspace Member Spotlight

March 6, 2023

This week we recognize Minoosh Zomorodinia, and her almost twenty-year practice as a photographer and interdisciplinary artist.

“Informed by my cultural background, religion, and politics, my work investigates the concept of “Self,” specifically how it relates to the environment. Inspired by nature, I borrow from rituals including walking, sometimes infusing humor. I integrate contradictory concepts into pieces that visualize struggles of the “self” by inserting my body into these moments of time and space. Recently I employed walking as a catalyst for my sculptures, which reference nomadic lifestyles, as well as colonialism. By tracking my paths using technology, I claim the ownership of the land, while representing a changed perception in the digital age and addressing transformation of memories into actual physical space absurdly.”

“Over several years I have referenced the natural elements in my work. The three channel video titled Resist: Air, Water, Earth, 2014 (above) is an ongoing project sometimes displayed as a photograph and sometimes as a video. I have been using water, air and earth as a metaphor of resistance, to demonstrate the challenges of daily life and global cultural conflicts. In the two side videos, I documented an ice cylinder using water from the San Francisco Bay, melting in different locations. In the middle screen, I use my body wearing a Chador (a traditional garment that devout Muslim women wear to cover the head and body). I hold it tightly so the wind or water don’t remove it while I’m walking backwards, entering the ocean. The video demands the viewer to watch the struggle, navigating my body with the camera, also while not paying attention to me.” (19:07 mins)

“Feelings produce different psychological states within the human being. Sensation (above) is the result from the air stimulation at different sites. I search for the self in nature while letting the wind touch the mylar to curve the shape of my body. I’m interested in the connection between my body and the landscape to express my feelings. My body merges with the landscape and the emergency blanket to integrate within the sky. Although the sense of touch is experienced through the lens it identifies resistance. The natural environment is a source of inspiration for me. Over the years, in search of the self in nature, I have attempted to create work using natural elements as material to explore connections between my body and landscape. In Sensation, for the first time the wind became an intuitive collaborator during a walk at the Djerassi Resident Artists site. I let the wind’s force define the shape of my body through an emergency blanket, a material that represents heat and protection for refugees in times of crisis. The video camera, the only witness to my actions, documents my struggles with the air that covers my entire body, making its force visible, caressing my form, emphasizing every movement and act of resistance. In attempts to merge my body with the landscape that surrounds me, the force of the wind is sometimes the winner. Sensation has been performed and documented at different sites, including the Marin Headlands and Talaghan, located in the Northeast of my hometown, Tehran.”

During the pandemic, Zomorodinia started to paint from the digital record of places that she physically experienced. In this series, Map of Walking, 2020 (above) she references archiving memory in space and time based on data saved through satellite maps. The gold leaf covers her physical movements in the place and addresses labor and the value of time and land. These paintings are from her residency at Recology AIR program, San Francisco, where she recorded her motions and time while scavenging trash from the dump to make art for her final exhibition. “I am interested in how technology forms memory through digital archiving, transforming invisible routes that exist as a memory into actual objects in abstract form. Is there any limitation?”

In her most recent series, Made Lands, 2021 (below) Zomorodinia re-forms and reshapes borders to reference historical monuments to labor and the memories of various localities, as well as representing topography in the digital age. The abstracted natural imagery is printed on leftover material with textures from the actual location. The printed images transform our perceptions of the natural environment in the new media age. She is interested in how technology forms memory through digital archiving, transforming invisible routes that exist as a memory into actual objects in abstract form. She asks, “How will the history of a place exist in the future?”

Minoosh Zomorodinia is an Iranian-born interdisciplinary artist who makes visible the emotional and psychological reflections of her mind’s eye inspired by nature and her environment. She employs walking as a catalyst to reference the power of technology as a colonial structure while negotiating boundaries of land. Her strollings sometimes reimagine our relationships between nature, land, and technology, while addressing the transformation of memories into actual physical space absurdly. Zomorodinia has received several awards, residences, and grants including the Kala Media Fellowship Award, Headlands Center for the Arts, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists’ Residency, Djerassi Residency, Recology Artist Residency, the Alternative Exposure Award, and California Art Council Grants. She has exhibited locally and internationally at Asian Art Museum San Francisco, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco Arts Commission, Berkeley Art Center, Pori Art Museum, Nevada Museum of Art, ProARTS, Untitled Art Fair Miami and many more. Her work has been featured in the SF Chronicle, Hyperallergic, SFWeekly, KQED and many other media outlets. She earned her MFA in New Genres from the San Francisco Art Institute, and holds a Masters degree in Graphic Design and BA in Photography from Azad University in Tehran. She currently lives and works in the Bay Area.

Bay Area Eco Artists: Where Art Meets Nature by Leora Lutz

Iranian-born Minoosh Zomorodinia also recently curated an ambitious group show titled “Between Lands” at Southern Exposure in the Mission District, which includes Iranian artists from the US and Iran. The exhibition featured several video works, inviting viewers to spend quality time with each piece, watching and listening. Much of the content was generated on the other side of the world, which further illuminated the point that ecological issues are global as well as local. The works invited visitors to “consider our attachments and anxieties in relationship with land and home when there is loss caused by war, fire, displacement, or other disaster,” stated Zomorodinia.

Through cinematography, collage, performance or mapping, the artists highlight the damage and demise of the landscape at the hands of humans. There was also an afternoon of tea and snacks held outside the gallery on the busy sidewalk, made from herbs and plants that can help curb the effects of air pollution caused by wildfire smoke. The problems caused by humans that damage land, erase history, or provoke health issues commonly stem from the need for territory or the ego’s need for power—desperation to live at the expense of our precious resources.

Exhibit uses art to reclaim stories and memories of place by Kathaleen Roberts, Albuquerque Journal

516 ARTS presents Counter Mapping, a group exhibition and series of public programs focusing on map-related artworks by 14 local, national, and international artists and art collectives. Co-curated by Viola Arduini and Jim Enote (Zuni Pueblo), the exhibition engages with geography, identity, politics, and the environment through painting, sculpture, photography, video, and installation. “Counter mapping” is a practice of mapping against dominant power structures to reclaim stories and memories of place.

Co-curator Viola Arduini speaks with Jamie Robertson, Minoosh Zomorodina & Cog•nate Collective about their artwork.

About this event

Join co-curator Viola Arduini and selected artists from the exhibition as they discuss their work, and how mapping and spacetelling inform contemporary histories, collective identities, and personal discovery.

Participating artists include Jamie Robertson, Minoosh Zomorodinia & Cog•nate Collective.

All That You Touch, Thacher Gallery

Professor Sam Mickey and USF students in conversation with artists Nicole Dixon, Conni McKenzie, and Minoosh Zomorodinia as they explore their creative processes and the roles of ecology and culture in their practices.

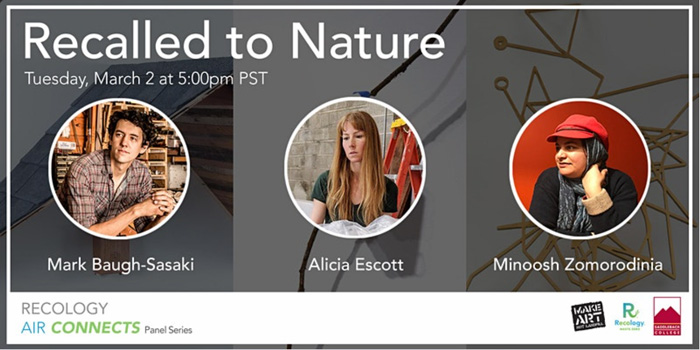

Recalled to Nature

The Recology Artist in Residence (AIR) Program in collaboration with Saddleback College hosted the second panel in our series, RECOLOGY AIR CONNECTS, on March 2.

Titled after Saddleback College’s virtual exhibition of work made at Recology curated by former AIR artist, Barbara Holmes, the panel “Recalled to Nature” brought together three vibrant voices from the Bay Area: Mark Baugh-Sasaki, Alicia Escott, and Minoosh Zomorodinia. In conversation with our moderators, Barbara Holmes and Victor Yañez-Lazcano, the artists discussed how they use art to explore the intersection of our social, political, and historical relationships to nature.

ABOUT ZAMIN PROJECT: Aggregate Space Gallery (ASG) presents Zamin Project, an intergenerational multi-faceted art project aiming to create a space for dialogue and connection between SWANA (South West Asia and North African) artists, curators, and art educators in the Bay Area and beyond. The first series of the Zamin Project is aiming to focus on the question of How can we create our own resources? by gathering SWANA artists, educators, and art leaders to develop a solution for enriching the community in the Bay area and beyond.

Interview with Whirligig

Whirligig is a platform for engaging in the lives and minds of creative individuals via the interview format.

Historically, a whirligig is both a torture device and a toy, characterized by its whirling or spinning nature.

Here, in these pages, Whirligig is a celebration of the creative life, which may sometimes be torturous, often leaves us spinning, but without a doubt is the most amazing playground.

A note on Emotional Numbness

یادداشتی بر نمایشگاه بیحسی

در مقدمۀ انقلاب هانا آرِنت میخوانیم: هابیل، قابیل را کشت و رُمولوس، رِموس را؛ در ابتدا جنگ بود. جنگ همان «کلمه» است که در یوحنا 2-1 :1 آمده است. کلمه یا Logos همه چیز است؛ حکمت، خرد، سخن و نظایر آن که دیالوگ هم ریشه در آن دارد. آرنت این گفتُگو را به جنگ ترجمه کرده است. گویی این عبارت سرنوشت محتوم ماست. جنگ داور نهایی است و متأسفانه حق با هابز بود که میگفت: پیمانها بدون شمشیر، الفاظی بیش نیستند. دست کم این برای ما که در ایران زندگی میکنیم، بارها عینیت یافته است؛ پیمانهایی که پاره شد و گزینههایی چون، تحریم و جنگ که روی میز گذاشته شد. کلاوزویتس در سالهای آخر عمر، درست حدس زده بود؛ جنگ چیزی نیست جز ادامۀ دیپلماسی با زبانی دیگر.

نمایشگاه بیحسی که با همکاری زنان اکو آرتیست و پلتفرم 3 فراهم آمده است و به تأثیرات جنگ بر روی روان انسان و زیست بوم میپردازد، ناظر بر کلمه، دیپلماسی و گفتوگویی است که اشاره شد بیحسی، زنان هنرمندی را از جاهای مختلف دنیا گرد آورده است که غالباً تجربیات شخصی خود از جنگ و تأثیراتش بر محیط زیست را در قالب ویدئو، مجسمه، عکس، نقاشی، چیدمان و آرتیست بوک ارائه میکنند. در بخشی از استیتمنت نمایشگاه، کیوریتورها، عاطفه خاص و مینوش زمردینیا، آوردهاند:

هدف، رسیدن به یک مکالمه مابین کیورتورها و هنرمندان و درنهایت به اشتراک گذاشتن آن با مخاطبان برای صحبت و بحث بیشتر پیرامون این موضوع [جنگ]، فرای مرزهای سیاسی و جغرافیایی است. ما بر این باوریم که هنر توانایی تأثیرگذاری بر ادراکات ، توسعه گفتگوی معنادار و آگاهی بخشی درباره موضوعات مهم را به عموم مردم دارد. گفتوگویی که در متن نمایشگاه، بازتاب پیدا کرده است گرچه از نظر کیوریتورها پیرامون جنگ است، به بیانی دیگر خود جنگ است. در اینجا جنگ سبب یک گفتوگوی عقلانی یا دیالکتیک به معنای عامش میشود و مسئلهای که آنرا با اهمیت میکند تجربیات شخصی غالب هنرمندان از جنگ است، بنابراین در این نمایشگاه، خرده روایتها که به واحدهای کوچک چون محلها، افراد، خانوادهها، نهادها و نظایرش تقسیم میشود، اهمیت پیدا میکند و در تقابل با روایت کلان تاریخی قرار میگیرد.

حال این روایتهای جامانده از تاریخ ثبت میشوند و باب گفتوگوی تازهای را باز میکنند که همیشه زیر سیطرۀ روایتهای کلان گم و یا نادیده گرفته میشدند. آلیس دابیل از هنرمندان نمایشگاه، محلهایی را در اثرش ترسیم میکند که خود تجربهاش کرده باشد. او میگوید: در این اثر من از نقشۀ نوپوگرافیک قدیمی فورت لوئیس و پایگاه نیروی هوایی مک کورد استفاده کردم […] و نقاطی را نشان دادم که دیگر وجود ندارند. JBLM یکی از چند تأسیسات نظامی در اطراف محل زندگی من در تنگۀ پیوجت در ساحل دریای سالیش است و این تاسیسات منظرۀ غالب در غرب واشنگتن است؛ همیشه ترافیک سنگینی در بزرگراه ایالتی شماره 5 وجود دارد و هزینههای اجتماعی ناشی از جنگ همواره وجود دارند. مانا صالحی از هنرمندان دیگر نمایشگاه ویدیویی را نمایش میدهد که در مرز ایران، ارمنستان و آذربایجان ضبط شده است و به جنگ قرهباغ مرتبط است.

منطقهای که سالها مورد مناقشه آذربایجان و ارمنستان بوده است و هر از گاهی آتش جنگ در آن شعلهور میشود و با میانجیگری ایران و کشورهای منطقه برای مدتی آرام میگیرد، اما مانا صالحی به این روایت کلان کاری ندارد و با حضور خودش در منطقۀ مرزی، تجربهاش میکند. یکی دیگر از آثار نمایشگاه « قیمت واقعی پلاستیک» نام دارد. جودیت سلبی لنگ و ریچارد لنگ، طی سالها با جمعآوری اسباببازیهای پلاستیکی، نظیر سرباز، سرخپوست، آدمفضایی، کابوی و دزدان دریایی از ساحل کهوئی به نحوی تاریخچۀ مناقشات جهان را روایت میکنند و نتیجه میگیرند که جنگ درون ماست، خواه این جنگ واقعی باشد، خواه ناسازگاری بر سر تصمیم گیریهای معمول زندگی. در این اثر هم خرده روایت از جنگ و هم تأثیر آن بر محیط زیست دیده میشود و آنها چون ریسایکل آرتیستها با جمعآوری این اشیاء دغدغههای محیط زیستیشان را نشان میدهند. نادیا اسکوردوپولو نیز در چیدمان «اسب تروا» از موادی استفاده میکند که در سواحلی چون ساحل ریدز، جمعآوری کرده است.

مری وایت، هنرمندی دیگر، 32 سال زندگی مشترکش با یک کهنه سرباز جنگ اتمی را در قالب عکس نمایش میدهد. ما راجع به بمب اتم، هیروشیما و ناکازاکی زیاد شنیدهایم. کلان روایتهایی که حس درد و رنج آدمی را نمیتوانند بیان کنند اما مری وایت با وقوف به این مسئله سراغ خود آن تأثیرات شیمیایی بر روی شریک زندگیاش میرود، کسی که شاهد کور شدن پرندگان و آدمها و ویرانی زیست بومها بر اثر بمب اتمی بوده است و نهایتا خود بر اثر تشعشعات هستهای جان میسپرد.

الیزابت کندی در اثرش بنام زاغۀ مهمات بولساچیکا نیز روی منطقهای مشخص که یادگار مخرب جنگ جهانی دوم است، متمرکز میشود. یک پایگاه نظامی آمریکا، 6 سال، ساحل، تالابها و تپههای بولساچیکا در کالیفرنیای جنوبی را تصرف میکند، پس از غیرفعال شدن پایگاه در سال 1948، آب تالابها که به اقیانوس آرام راه دارد آلوده میشود و زیستگاه صدها گونه پرندۀ آبزی و گونههای مهاجر در خطر میافتد. از آن روز تا به امروز این محل در حال پاکسازی است و پیشبینی میشود که تا سال 2078 ادامه یابد. آندره سینگر در اثر سرامیکیاش با نام خانوادۀ هودو که یادمانی است برای بازماندگان، نگاهی شخصی شده و متفاوت به جنگ دارد. همه از این عبارات کلی که از معنا خالی شده شنیدهایم: جنگ ویرانگر است، جنگ جان آدمیان را میگیرد، جنگ محیط زیست را نابود میکند و نظایرش. اما همۀ اینها بر روی چه کسانی تأثیر دارد؟ جنگ بازماندگانی هم دارد که کسی برای آنها یادبود نمیسازد. آنها که زنده ماندهاند و مصیبت را به تنهایی به دوش میکشند.

در ویدئوِ «بِپَر» کار مشترک گزل سامیزای و لبخند الفتمنش، دو هنرمند افغان و ایرانی، دو همسایه، دو همزبان، با اشتراکات و افتراقات فرهنگی، تاریخ خرد و روایت فردی را بهتر میبینیم.در این ویدئو اثرات جنگ و پدرسالاری در مسیر زندگی یک زن، از کودکی تا بزرگسالی در بازی لی لی نمایش داده میشود. آنها میگویند: توجه ما معطوف به این است که چگونه انتظارات فرهنگی و تأثیرات جنگ، مرزها را از میان برمیدارند و بر زنان، فارغ از محلشان تأثیر میگذارند. کاملا پلت در «دو لتۀ جزیرۀ پرندگان» دو قطعه عکس از جزیرهای در دریاچۀ المندورف در سال 2019 به فاصلۀ چند ماه، برداشته است. در استیتمنت هنرمند اشاره میشود که جزیرۀ پرندگان نامی است که نسلهای پیشین جامعۀ محلی بر آن گذاشتهاند و زیستگاه نوعی حواصیل است و محلی با ارزش بومشناختی و فرهنگی ماندگار است. هم راستا با جابجاییهایی که برای اجتماعات و زیستبومها در جهان رخ میدهد، پایگاههای نظامی و وزارت کشاورزی ایالات متحده، نقشههایی برای نابود کردن حواصیلها کشیدهاند. این دو قطعه عکس، یکی مربوط به پیش از تخریب است و یکی پس از نابودی گلها و لانههای پرندگان. این اثر به لحاظ شناخت ما از تاریخ یک محله که در هیچ کتاب تاریخیای ثبت نمیشود با اهمیت است و دغدغههای محیط زیستی هنرمند را نشان میدهد.

در اثری دیگر، کاتیا گروکاوسکی در ویدئویی به مرور تاریخچۀ خانوادهاش میپردازد. پروژه با تمرکز بر روایت حول شخصیت مادربزرگ، تنها بازماندۀ گروکاوسکی که از کهنه سربازان جنگ جهانی دوم است، شکل میگیرد. این روایت همان تاریخ خرد است که جای دیگری نمیتوانیم سراغی از آن بگیریم. در آرتیست بوک نانت وایلد نیز به انفجاری در خیابان المتنبی بغداد به تاریخ 5 مارس 2007 پرداخته میشود. انفجاری که برای مدتی ارزش خبری داشت و نه تاریخی. در چیدمان سارا معدندار با عنوان «به یاد عزیز»که برگرفته از خاطراتش از خانۀ مادربزرگش است، به شکلی دیگر با یک روایت شخصی از جنگ مواجهایم. او که به آمریکا مهاجرت کرده است پس از اولین سفرش به ایران همهچیز را دست نخورده به مانند زمانی که مادربزرگش زنده بود، میبیند. انگار که زمان در لحظهای مشخص از حرکت باز ایستاده است. خاطرات، اشیا و پرترۀ دایی احمدش که وقتی 17 سال بیشتر سن نداشت در جنگ ایران و عراق شهید شده بود. شیرین خلعتبری در عکسی با عنوان «ردپا» تصویر امروزی شهر باستانی اور را ثبت میکند. او در راه رسیدن به بقایای اور با دود غلیظ پالایشگاهها، پلاستیک و نخالهها رو به رو میشود.

آثاری که در اینجا از نمایشگاه «بیحسی» به آن پرداختیم، به روایات شخصی اهمیت میدهند که میتواند موضوع تاریخنگاری جدیدی باشد که در دهۀ 1970 با نام «میکروهیستوری» به وجود آمد. این روش تاریخنگاری به دلیل ویژگیهای آن ارتباط نزدیکی با علوم اجتماعی دارد و مورخان با استفاده از اسناد به دست آمده از آن، به انگیزهها، تصمیمگیریها و عملکرد جامعه و بازتاب آن در محیط مورد تحقیق پی میببرند. میکروهیستورینها عقیده دارند که موضوعات کوچک منابع اندکی دارند که بهتر میتوان آنها را تکمیل کرد و در کنار هم گذاشت و به کمک تمامی اجزای بازسازی شده، تصویر نهایی را بصورت واقعی و به دور از فرض و گمان، تکمیل کرد. آنها با شناسایی اجزای کوچک و بررسی ارتباط بین پدیدههای مختلف درمییابند، مردم چگونه زندگی میکنند، تحت تأثیر چه شرایطی قرار دارند و در مواجهه با وضعیتهای ناشناخته چه واکنشی نشان میدهند. به زعم آنها این یکی از راههای برون رفت از بحرانهای اجتماعی و افزایش مشارکت اجتماعی نقاط دور و نزدیک است.

این شیوۀ نگاه به تاریخ را میتوان مقابل آرشیو کلاسیک قرار داد که بسیار مورد تردید قرار میگیرد و میل به تفسیر نادقیق و از منظر قدرت به وقایع دارد. گفتگویی که پیشتر از آن صحبت شد در قالب چنین نگاهی محقق میشود؛ گفتگویی که خود جنگ است و دارای مفاهیمی درک شدنی است. در استیتمنت هنرمندان بدون مرز که در نمایشگاه بیحسی اثری از آنها با عنوان «جنگ و صلح» نمایش داده شد، میخوانیم: ما باور داریم که هنر و هنرمندان زبان مشترکی دارند و میتوانند انسانها را گرد هم آورند. اجازه دهید این نقل قول را کمی تغییر دهیم. ما باور داریم که زبان مشترکی که هنرمندان این نمایشگاه را گرد هم آورده است «جنگ» است، گرچه نظر کیوریتورها و هنرمندان این نمایشگاه، جز این باشد.

#بام_گردی

دبیر: محمد شمس

نویسنده: ماهور طوسی

VR SHOW & TELL ARTCAMP

Minoosh Zomorodinia is our tour guide in her virtual space that she created during her residency in the Art Camp in 2021

VIDEOS OF RESISTANCE

After Hope: Videos of Resistance is an exploration of the expressions and legacies of hope within contemporary art. The exhibition consists of more than fifty short, single-channel videos, drawn from recommendations by artists, curators, and organizations across the world. The result is a six-hour looping chronicle of hope that is eclectic in nature, rather than unified by a single narrative. Click on the links below to read more about each work and how the artists and recommenders responded to prompt to think “after hope.”

A SPECTRUM OF POSSIBILITY IN UNSETTLING TIMES

An ESSAY BY LAURA ELIASIEH

Tunnels of the Mind Video Art Projection in Time Square

June 10-15, 2020

WATCH LIVE JUNE 12-13 9pm

Wander Woman 2 – Curated by Rea Lynn de Guzman

Curated by Rea Lyn 8, 2020, 6-8pm

Exhibition Dates: May 8 – 23, 2020

SF Camerawork Gallery Project Room

Link to live presentation

Wander Woman 2, the second iteration of Wander Woman, provides an empowering and engaging platform for Bay Area-local, APA immigrant women of color, who vary in professional backgrounds from emerging to established. Its mission is to highlight the artists and their work, and to amplify their voices by presenting significant conversations surrounding issues of equity, gender roles, and underrepresentation. Further, it aims to foster deep connections within the community and beyond.

Lead Producing Artist: Rea Lynn de Guzman

Exhibiting Artists: Kimberley Acebo Arteche, Aynur Girgin Westen, Kiana Honarmand, Kacy Jung, Mido Lee, Joyce Nojima, Azin Seraj, Pallavi Sharma, Pamela Ybañez, and Minoosh Zomorodinia.

Wander Woman 2 is presented by SF Camerawork and the Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center as part of the 23rd annual United States of Asian America Festival 2020: FINDING KINSHIP.

Experiments in the Field: Creative Collaboration in the Age of Ecological Concern-Berkeley Art Center

Curated by Svea Lin Soll

Experiments in the Field: Creative Collaboration in the Age of Ecological Concern presents artworks by Adriane Colburn, Alicia Escott, Stacey Goodman, Chanell Stone, Livien Yin, and Minoosh Zomorodinia, with a public participatory work by the Bureau of Linguistical Reality.

The ways we have come to know about our environment and the magnitude of the climate challenges we face has frequently been framed through visual modes such as satellite imagery, documentary photographs or simulation models. While scientific objectivity is crucial to our formal understanding of climate change, art offers a range of discursive, visual, and sensual strategies to connect with these complex issues.

Art in its many forms has always documented human experience, imagined new futures, reoriented our perspectives, and sparked cultural change. The artists in this exhibition expand on the particularities of site, ownership, history, representation, perception, public domain, and stewardship. They explore deeply personal and cultural narratives through a transdisciplinary approach, working with performance, video, sculpture, writing, activism, scientific and historical data, and social engagement — a decisively human context that allows art to share meaning and transform values. While addressing ecological concerns, this exhibition is also a conceptual centrifuge for exploration and future action.

Artists: Bureau of Linguistical Reality, Adriane Colburn, Alicia Escott, Stacey Goodman, Keith Secola, Chanell Stone, Livien Yin, Minoosh Zomorodinia.

Interview

Exhibit at Berkeley Art Center speaks to our imminent eco-catastrophe

A diverse group of artists speak in a range of voices, often obliquely, to our current state of imminent eco-catastrophe.

By Marcia Tanner

Experiments in the Field: Creative Collaboration in the Age of Ecological Concern, the timely, engaging and provocative exhibition open through Sept. 26 at the Berkeley Art Center (by appointment only), presents work in a variety of forms and media by a diverse group of East Bay artists: The Bureau of Linguistical Reality, Adriane Colburn, Alicia Escott, Stacey Goodman, Chanell Stone, Livien Yin, and Minoosh Zomorodinia.

Organized by Berkeley-based guest curator Svea Lin Soll, and elegantly installed in BAC’s tranquil, wooded oasis, the show speaks in a range of voices, often obliquely, to our current state of imminent eco-catastrophe.

Alicia Escott and Heidi Quante are the collaborative duo behind The Bureau of Linguistical Reality, a public participatory project dedicated to inventing new language to describe or re-frame contemporary experience. Working with artists in the exhibition and other BAC community members, they coined the neologism spectramergensee, a portmanteau word that could well serve as the show’s subtitle.

Its lengthy, aspirational, if somewhat overloaded, definition is mounted on posters in the gallery’s patio. Here’s part of it: spectramergensee: The way that a crisis and a natural disaster may bring people together, and out of their routines; entering into or emerging out of the cocoon of private space into a new sense of community through disruption.

Adriane Colburn’s 2019 colorful, mixed media sculptural installation The Spoils (see top photo), resembles the contents of a giant pinball machine escaped from its container. Its labyrinthine form and disquieting mix of data points, unrecyclable materials and models of endangered animals suggest a map of disaster based on global commerce: a precarious, unwinnable game sabotaged by its own flawed, unsustainable system.

Livien Yin’s mixed media sculptural weaving Bombyx Papaver is—for this reviewer—the most subtle and compelling piece in the show. Beautiful and evocative in itself, its form suggests the Guzhen, a stringed Chinese musical instrument called by Westerners “the Chinese zither”. Its title, Bombyx Papaver, refers to the Linnaean classification for the silkworm and the opium poppy flower.

All the materials it’s made of—silk thread, cotton, wool, white opium poppy seeds, maple wood and peach blossom branches—allude to aspects of historic Western imperialistic plundering of Chinese natural resources and culture, and the West’s economic exploitation of Chinese people and their labor.

Bombyx Papaver is one in a series of the artist’s riffs on the Wardian case: the sealed glass terrarium, invented in 19th Century England, that made it possible to transport live plants (invasive, destructive organisms included) safely across the seas. The Wardian case radically transformed international commerce and local ecosystems. Among other things, it allowed England to break the Chinese monopoly on tea by bringing tea plants to its colony, India, for cultivation.

Not all the works in the show have so many multilayered allusions embedded in them, but they’re rewarding nonetheless.

Qanat, Minoosh Zomorodinia’s mixed media sculptural installation, combines found metal scrap salvaged from San Francisco’s Recology (the solid waste recovery center) with video projection, the sound of trickling water, and ice, to evoke a desolate post-nature irrigation system in a “garden” made of discarded metal and electronic media. Qanat is the Persian name for “a gently sloping underground channel to transport water from an aquifer or water well to the surface for irrigation or drinking.” The piece suggests dark days ahead for our own water system in parched, drought-ridden California.

A series of arresting, lyrical black and white photographs by Chanell Stone portray Black people in urban American settings, amidst the remnants of the natural world that still exist around them: scraggly trees and shrubs, blighted back yards with foliage struggling to survive amidst rubble. For the artist, these images both dramatize the alienation from nature forced upon Black people by American racist history, while documenting her, and their, attempts to reconnect them with it. Despite their surface bleakness, these images are luminous, tender acts of reclamation.

Stacey Goodman uses drone videography as a paradoxical medium. It’s potentially insidious, a technology for total surveillance and control, further estranging us from nature and each other. Yet it can also reveal our human relationships to the natural world.

Goodman’s three drone-made videos—This Tree—Devotion, This Tree—Mastery, This Tree—Communion—follow the artist himself, from a great height (God’s eye view?), as he crawls on his belly toward a tree growing on a grassy hillside.

Goodman’s slow, agonizing treks are reminiscent of the punishing urban crawls performed by another Black American artist, William Pope L., but with a radically different intent. Pope L. lays his body on the line, dragging himself along on filthy city streets, to enact the enduring legacy of pain, subjugation and humiliation suffered by black bodies in our nation for over 400 years.

In contrast, Goodman falls on his knees to embrace the earth, with a living tree as his destination. His tests of endurance are a kind of Hadj or pilgrimage: a spiritual journey toward interconnectedness. Embodying a longing to merge with all earthly life, his actions are a form of worship, and of hope.

Alicia Escott’s Coastal Live Oak installation is the most literal work in the show. It’s a harvest of oak tree limbs and branches from the glade surrounding the gallery, festooned with inorganic detritus left behind, accidentally or deliberately, by human visitors. There are jewelry, hair ornaments, copper wire, even a cell phone, entangled in the branches. The piece fills a wall, decoratively, but doesn’t do much to stretch the imagination. Not mine, anyway.

In bringing these artists’ work to our attention, Experiments in the Field spurs viewers’ imaginations toward creative responses to the linked environmental and socioeconomic messes we’ve made of things. Go see it in person, if you can, before September 26.

Women + Teaching + Trauma

In this third installation of MixTapes, SoEx Curatorial Councilmember and Artist Minoosh Zomorodinia DJs the internet for you with selections from online projects to sustaining texts to peripheral inspirations. Get to know her creative practices from these jumping off points.

Explore the linked tracks here

A Review by Sarah Hotchkiss

Through a San Francisco Peephole, a Glimpse of Video Art in Iran

Hofreh curated by Minoosh Zomorodinia. Iranian Artists: Atefeh Khas, Tara Goudarzi, Setareh Hosseini, Nooshin Naficy, Raziyeh Goudarzi, Majod Ziaee.

San Francisco’s Peephole Cinema is so unassuming I accidentally walked past it twice. But that’s part of the magic of this unostentatious (and miniature) screening space, established in 2013 by artist Laurie O’Brien and run today by Sarah Klein: its ability to blend in with its surroundings. Three doors up from 26th Street, about three feet above ground level, a dime-sized peephole in the side of the purple-painted staircase to 280 Orange Alley is a portal to other worlds.

That transportative feeling is even stronger with the cinema’s current program. Curated by local artist Minoosh Zomorodinia, Hofreh (Persian for “hole,” “cavity” or “eye socket”) presents six silent, experimental short videos from contemporary Iranian artists. Each one is a study in effective brevity, none longer than a minute, and all tell beautifully composed stories of identity, gender and human relationships to nature.

Viewed in January 2020, just days after the United States killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, amid chatter about “World War III” and anti-war protests, this short-term and small-scale program deals in specificity. Hofreh is six videos from six artists, on loop 24 hours a day. It presents the concerns of artists, ordinary Iranian civilians, who we rarely get to hear from when gross overgeneralizations, glossed-over histories and terrifying threats rule the airways.

The program opens with a literal splash in Tara Goudarzi’s Offering. Action comes near the end of the 30-second video, and it occurs suddenly (potentially violently) as what looks like dark mud splashes across the artist, who stands still in a white veil. In a statement about the Offering series, which Goudarzi performs and documents in a variety of natural settings, she writes of the veil as a companion: “We have always been together, ever since I was nine, sometimes out of divine love and sometimes out of hatred.” The offering seems to be her long relationship with this garment, which she now enjoys for “its purity, and its plainness, its whiteness.”

A few videos later in the loop, Nooshin Naficy’s A Stone Embryo appears as the most direct complement to Goudarzi’s short. Instead of nature “acting” on a lone female figure, this video features a woman in motion. But even as she climbs a rock formation to cradle a stone, the camera pulls back, shrinking her figure against the dramatic landscape.

In Zomorodinia’s curatorial statement, she makes reference to the encroachment of urban development on natural space in Iran, relating the imposition of humanity on nature to the societal expectations placed on Iranian women. This, she writes, “causes many to leave the country so they can live freely,” allowing them to escape either family demands or social pressures.

Setareh Hosseini captures this state of in-between-ness in her own stop-motion video Bubbles, which shows a woman’s image over a sky, spinning as if presenting herself from different vantage points. Clear “bubbles” dot the space around her, ultimately landing on her face and erasing her image. In a poetic accompanying statement, Hosseini writes of “girls suspended between staying and leaving,” “girls left back,” and “girls of waiting.”

While Majid Ziaee’s Hasht (Persian for “eight”) and Razieh Goudarzi’s Mirror Sky are no less ambiguous, they document an often playful agency within nature. Ziaee’s stop-motion video of just eight frames begins with him reclining and ends with his body “supporting” an angled desert tree, mimicking the character for “eight” (٨). Razieh Goudarzi’s 40-second video zooms in, keeping the frame tight on a hand holding a round mirror. As the figure walks across a leaf-covered ground, a surrealistic view of empty branches shifts across the mirror’s surface. We get to look up while looking down—and while also looking through a round hole of our own.

The everyday sounds of Orange Alley become the score for anything showing in Peephole Cinema. On the morning of my visit, that meant nearby jackhammering and the occasional passing car. The contrast between image and audio doesn’t feel too jarring—we’re used to looking at things on pocket-sized screens while tuning out the surrounding world. What’s more noticeable is the physical effect of viewing (I had to bend in half to put my eye to the hole). Sustaining that pose, even for a relatively short span of time, makes one acutely aware of the peephole as a tool of both surveillance and privacy. To look through it is to be vulnerable, a fitting exchange between artist and audience.

Reflecting this exchange is the most sublime video in Hofreh, Atefeh Khas’ Friendship. In it, a bird sits on a woman’s shoulder and delicately dips its beak into her ear (a bodily hofreh, if we’re paying attention). The woman rubs her ear in turn, and the bird shifts its eye directly toward the camera, a fourth-wall break by an unwitting actor.

Just as the jackhammer and the cars can’t be fully muffled, it’s impossible to watch Hofreh without placing the program in the context of the present moment. Its artistic merit remains, but its relevance increases. Because specificity, even in the smallest of doses, speaks so much louder than we often care to hear.

ecoconsciousness fall 2020 online + billboard show

What does it mean to have an ecoconsciousness? The works here offer multiple answers to that question. ecoconsciousness measures our interconnectivity with the natural world. It celebrates our links to the animals with whom we share the planet, to the trees, fruits, vegetables, herbs and insects that make life possible, to the land and waters that bear witness to our best and worst impulses and to the ecological systems that sustain us all. It encompasses our awareness both of the beauty of nature and the devastating horrors created by our efforts to exploit it. It manifests itself in artworks that bring the perilous consequences of our actions to our attention through striking images, immersive installations, evocative performances and rituals and practical proposals. It engages with fields as diverse as science, technology, poetry, politics, history, anthropology, art history and futurism. And it poses questions about our place in the cosmos with wit, sorrow, anger and hope.

“Make Room For Me” at Little Berlin

Natalie Sandstrom reviews “Make Room For Me” at Little Berlin, a video and photography heavy show featuring eleven Middle/ Near Eastern queer and femme identifying artists. Catch this show before it closes on June 29th, 2019!

The premise behind Make Room for Me is an ambitious one: highlight the work of queer and femme identifying artists from the Middle/ Near East. The scope of this ambition, however, did not overwhelm curator Sarah Trad. Trad managed to cull the works down to a succinct and challenging bunch – a range that highlights video, installation, photography, performance, and zines – while maintaining the thesis of the show: visibility.

Make Room for Me features 11 artists: Yasmina Hilal, Alia Hijaab, Sholeh Asgary, Minoosh Zomorodinia, Mette Loulou von Kohl, Donia Jarrar, Kris Rumman, Nishat Hossain, Noorann Matties, Samar Ziadat, and Sarah Alfarhan. The works are spread over Little Berlin’s industrial-feeling space, with photographs hung on walls, installations tucked into corners, and videos presented on screens of various sizes and types. This range gives the gallery a freshness as you move through it, and the works are spaced in such a way that you have the required area to inspect and appreciate each artist’s group of works. For a show of this range and theme (the title is, after all, Make Room for Me), this space is essential, and I was excited to see it present. Surprisingly, this contemplative space was even there on the crowded opening night.

I most appreciated this open quality when I spent time with Ahia Hijaab’s video – to me, the star of the exhibition. “Al Ghorba” (2018, 6:07) is presented on a very small screen, with a single set of headphones. This creates an intimate experience between viewer and video. The brief artwork tells a story of a woman moving from Syria to an unknown Western city (perhaps inspired by the artist’s own journey from Syria to Vancouver). It is a beautifully animated video, composed of vibrant colors that bring the illustrations to vivid life. The hypnotic voiceover gives a great sense of rhythm to the work for those of us who do not know Arabic (the words are also illustrated on-screen), and, I would assume the voice is comforting still to those who do. The video tells a familiar story of moving away from home and family, but of course has the added layer of the anxiety of international moving, guilt of leaving one’s loved-ones, and anxiety regarding the safety of the home nation. Ultimately, the work is a moving and thought-provoking story of immigration and family, delivered in an elegant and visually satisfying package.

Across the gallery, Minoosh Zomorodinia’s videos (“Sensation III” and “Resist”) are similarly compelling. “Sensation III” takes a more meditative bent, showing someone on a hilltop, their figure covered with a silver heat blanket held against their body by the wind. There is a kind of sublimeness to the work: the covered person is only identifiable as a woman by the faint outline of breasts beneath the blanket; she is alone with the wind. Importantly, the heat blanket is also commonly known as an “emergency blanket” or “survival blanket” – nomenclature which adds a layer to the work by reemphasizing the solitude and vulnerability of the female body in this open space. It is quite meditative to experience, and leaves you with an imagined sense of the wind blowing against your own (gendered) body.

Nearby, a selection of photographs from Nooran Matties cannot help but attract viewers. They have a grungy feel about them, as though the camera lens was dusty, or the photos were developed under imperfect circumstances. This patina is alluring, and, coupled with the focus on banality (applying makeup, bending over, a sleeve of tattoos…), is enchanting. Perhaps the exposed quality of the works is what is so reminiscent of another female photographer, Deana Lawson. I was particularly drawn to the vulnerability of “Untitled III,” which depicts the artist bending over, hair hanging toward the floor, back and neck exposed, all set within a clothing-cluttered room. The relatability of the image is fantastic – viewers may imagine themselves in their own rooms, drying their hair after a shower, a connection made all the easier by the lack of a face.

This facelessness was a common theme in the show, running across the works of Zomorodinia, Matties, Asgary, Rumman, and – at times – the performance from von Kohl. In such an identity-focused show, this was an interesting choice. Perhaps the idea was to make the works relatable, or to comment on the loss of individuality that comes with stereotypes of gender and exoticism. Regardless, it is an effective choice that still gets at the overarching idea of vulnerability. Of course some works broke this mold, such as the screenshots made of layered photos from Nishat Hossain, which feature her face repeatedly.

The performance by Mette Loulou von Kohl (at the opening on June 8) straddled this facial in/visibility. In “No one likes an ugly revolutionary,” the artist transitioned between covering and uncovering her face in a punchy performance that was both poetic and balletic, urgent and reflective. In her exploration of generational storytelling, identity formation, and the sexualization of brown female bodies (such as Palestinian plane hijacker Leila Khaled, and others) von Kohl delivered an energy that left the audience silent at the end of the performance. It was unclear whether this silence was due to anticipation or digestion – or, most likely, a mix of both. This thoughtfulness characterizes the show as a whole, an exhibition which demands a slow pace and thoughtful consumption, and rewards those who undergo this process.

“Make Room for Me,” Little Berlin, June 8 – 29, 2019

Note: Little Berlin Gallery is only open on Sundays from noon to 4 PM

Forty Years After the Revolution, Iranian-American Artists Look Back

By Jonathan Curiel, SF Weekly, March 6,2019

In her video series, Sensation, Minoosh Zomorodinia sets up a camera in various windswept terrains and walks in front of it. Then she wraps her entire body, including her face, in a shiny emergency blanket and waits for the wind to push her. Zomorodinia pushes back. Simply by standing there and resisting — even as the wind rips off some of the blanket’s material — Zomorodinia becomes a kind of covered-up, sculptural combatant. The work is funny in the same way that Buster Keaton’s and Charlie Chaplin’s physical comedy is funny. But some art-goers may view Sensation as a subtle political work, especially since it’s included in a new San Francisco exhibit, “Part and Parcel” at the San Francisco Arts Commission main gallery, that examines the 40th anniversary of Iran’s religious revolution.

Zomorodinia, who was born and raised in Iran and now lives in Albany, filmed the work for Sensation in several Bay Area locations and also at Taleghan Mountain, a snowy peak north of Tehran. She filmed the scenes before she knew her work would appear in “Part and Parcel,” and her work at the San Francisco Art Commission gallery is — for the first time — in two channels.

“I don’t make art for political reasons, and I never consider myself a political artist … and I never made this piece with an attempt to be political,” Zomorodinia tells SF Weekly. “Part of my work is actually funny. I make this art intentional because I’m using this idea of using a tiny bit of movement and action. But it’s humorous.”

The exhibit’s three other featured artists — Tannaz Farsi, Gelare Khoshgozaran, and Sahar Khoury — are also West Coast Iranian-American figures. Farsi, who lives and works in Eugene, Ore., will be at the gallery on Saturday, March 9, 1-3 p.m, to read from The Names, her art project that unites the names of important Iranian women.

Curated by celebrated San Francisco artist Taraneh Hemami, the last day of “Part and Parcel” (March 30) segues into “Once at Present: Contemporary Art of Bay Area Iranian Diaspora,” a major exhibit at Minnesota Street Project that Hemami and Kevin B. Chen co-curated. Hemami, Farsi, Khoshgozaran and other prominent figures are also participating in a March 30 panel (1-2:30 p.m.) at San Francisco State, “Contemporary Practices: Visual Artists of the Iranian Diaspora,” that’s part of a wider two-day academic conference at the university.

As part of “Part and Parcel” last month, Zomorodinia led a group of people — some of them wearing the same type of emergency blanket she wears in her Sensation series — along streets near San Francisco City Hall in an event that emphasized body movement and ideas around belonging. When she has filmed Sensation, Zomorodinia is usually by herself. She prefers it that way so she can be more herself, without the influence of onlookers. The compilations in “Part and Parcel” are minutes long, but Zomorodinia will make hours of footage to get the right moments for her exhibited work. Staying as still as possible is part of what Zomorodinia says is performance art.

“I improvise, but mostly what I try to capture is a performance that doesn’t need any edits,” says Zomorodinia, who earned her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, where she decided that performance art would be a specialty. “It’s so hard to be a live performer because I always have this feeling that I’m not immersed in a community. In that school, I don’t think they had seen Muslim people in art, so I said, ‘I’m going to use my body.’ I had a lot of struggles to show myself. But I thought it was important for me to react to what I feel around myself as an artist. I wanted to be an environmental artist, but I didn’t want to create a lot of objects.”

So Zomorodinia turned herself into one for the work that is Sensation.

“Part and Parcel,” through March 30 at the San Francisco Arts Commission main gallery, 401 Van Ness Ave. Free; 415-252-2255 or sfartscommission.org

The art of leaning against the wind inside an emergency blanket

By Sam Whiting, San Francisco Chronicle, February 5, 2019

The western wind blows hard when you’re facing into it atop a ridge on the Marin Headlands, and harder still when you are holding up a Mylar emergency blanket that sticks to you like cellophane, until little pieces of the blanket start to tear off and fly away.

That is the obvious message in Minoosh Zomorodinia’s video installation “Sensation,” which opened Jan. 25 at the San Francisco Arts Commission Galleries. The less obvious message is that this blanket is what refugees receive from the Red Cross upon arrival in the United States, and by using it as a sail Zomorodinia feels the intense pressure pushing her back and struggles for the strength to resist it.

“A couple of times I was about to fall off the cliff,” says Zomorodinia, 46, an interdisciplinary artist from Albany who grew up in Tehran. She submitted “Sensation” to the group show “Part and Parcel,” sponsored by the San Francisco Arts Commission.

Curated by Taraneh Hemami, who teaches at the California College of the Arts, the exhibition is timed to the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. “Four contemporary artists of the Iranian Diaspora examine geographies of belonging,” is the subtitle, with the other three being Tannaz Farsi, Gelare Khoshgozaran and Sahar Khoury.

“My practice is about my connection in nature,” says Zomorodinia, who was 7 when the Shah of Iran was exiled. “Some people see it as political, but it is just an expression of my feeling about everything that is around me.”

What Zomorodinia likes to feel around her is wind, which has played a role in several of her pieces. For this one she ordered a dozen of the emergency blankets online, while in the Djerassi Resident Artists Program in the hills west of Woodside, in 2016.

The artist then hiked up on a trail to feel the full brunt of the autumn wind blowing off the Pacific. She set up her video camera on a tripod and stood there for at least four hours to get one usable minute, with the wind blowing just right.

At the same time she was an affiliate artist at Headlands Center for the Arts, so she took her blanket there and got blown twice as hard as at Djerassi. To finish the piece, she brought her human weather-vane act to her native Iran and set up her camera at Mount Taleghan, immediately after a snowstorm.

“That was the shortest one, maybe 45 minutes or an hour,” she says. “It was too cold to stand there any longer.”

The three locations were edited into several short clips that project onto screens on opposite walls in an enclosed gallery, forming a two-channel video. While seated on a bench on the perpendicular wall, a viewer can see both channels at once and watch Zomorodinia on a continuous loop of walking to her perch, covering herself with the blanket and then standing there with her arms out to her sides to form a T as she gets blown away, then goes back to start over.

In this sense it is an action film, with the soundtrack blowing a gale.

“She’s really fighting to stay upright,” says Meg Shiffler, director of SFAC Galleries, while seated on the bench, watching the show. “The wind pushes the blanket against her body and she pushes back against invisible forces.”

“The western wind blows hard when you’re facing into it atop a ridge on the Marin Headlands, and harder still when you are holding up a Mylar emergency blanket that sticks to you like cellophane, until little pieces of the blanket start to tear off and fly away.” Sam Whiting

Go-to galleries: SFAC Galleries

By Sura Wood, Bay Area Reporter, February 1, 2019

The year is off to a thought-provoking start at local galleries and nonprofit spaces, with artists zeroing in on topical issues from the environment to immigration.

San Francisco Arts Commission Main Gallery: “Part and Parcel” This spring marks 40 years since the Iranian revolution, whose aftermath displaced over 3 million Iranians who migrated to the West. The largest populations put down roots in the U.S, with half settling in California. It would seem there could hardly be a more auspicious moment to invite four contemporary artists of the Iranian Diaspora to participate in an exhibition that explores the meaning of belonging and the desire to achieve it.

Interdisciplinary artist and writer Gelare Khoshgozaran, who was born and raised in Tehran and is based in L.A., contributes “Diplomatic Relations,” which consists of a slide projection, its contents culled from her family’s photography archive, and a bookshelf stacked with packages lit from within. The installation, she has said, was made in collaboration with her parents who shipped her home library in Iran to her California studio. She characterizes her relationship with her parents as “an intimacy under constant surveillance, state violence and the severance of diplomatic ties. The impossibility of closeness — regulated by X-ray machines, customs, and sanctions — negotiated in the silence of queer life unspoken of.” In a metaphoric two-channel video, Minoosh Zomorodinia depicts herself standing alone, almost entirely wrapped in silver foil like a Greek statue awaiting unveiling, braving headwinds in sweeping landscapes, one a cliff overlooking San Francisco Bay, another at the edge of icy mountain slopes. Sahar Khoury’s personal sculptures include games of chance and strategy, and reflect on the nature of time, while Tannaz Farsi looks at historic Iranian cultural objects, comparing how they’ve been interpreted, then and now. Two large photographs, “Strata of Empire (Vestige)” and “Strata of Empire (Relic),” ruminate on the vagaries of empires through a limestone fragment discovered at the ruins of Persepolis, where sculptural carvings and reliefs don’t portray women or acknowledge their existence. In what might be a construed as a corrective, a wall work by Farsi pays tribute to notable Iranian women — writers, translators, martyrs and poets — their names spelled out in a font reminiscent of ancient Arabic calligraphy. (SFartscommission.org; through March 30.)

Taraneh Hemami, who curated the SFAC show, has also collaborated with Kevin Chen on “Once at Present: Contemporary Art of Bay Area Iranian Diaspora,” a group exhibition that will be installed in several spaces at Minnesota Street Project, March 30-April 20.

Go-to-galleries

“Horizon to Horizon” Art Project Transcends Borders

Horizon to Horizon is a collaborative art project that connects high school students from East Palo Alto, California and Khorramabad, Iran together in dialogue. Curated by artist and lecturer Ala Ebtekar, the project was led by this year’s Art, Social Space and Public Discourse Artist in Residence Minoosh Zomorodinia and her collaborating partner Tara Goodarzy. They worked in parallel over the last year, facilitating discourse between two groups of students and empowering them through technology to work as a team with peers from across the globe.

Students responded through text and textiles to prompts from Minoosh and Tara that involved prescient matters affecting each of the two groups on a local as well as a global scale. The students provided articles of clothing or textiles from home that had an intimate, familial story. They then constructed physical spheres made with this material, considering the body and the movement of these shared, celestial orbs.

Furthermore, they set up a framework for students to chat in real time and in recorded messages passed back and forth, all steered by their own questions intentionally kept separate from the instructors. This studio, built from conversations, resulted in a series of performances that are still growing in tandem. Projects like these are perfect examples of citizen diplomacy that can lead to more understanding in these fraught times.

Visualizing Time: Raheleh Minoosh Zomorodinia

By Rose Lou NEBULAE MAGAZINE September 1, 2018

Raheleh Minoosh Zomorodinia is a San Francisco based multimedia artist working across several platforms of time and space. Zomorodinia earned her B.A. in photography and M.A. in graphic design from the Art and Architecture Azad University in Tehron before receiving her M.F.A. in new genres from San Francisco Art Institute. Her work often deploys complex visualizations of light, humor, and time, as she has experienced them while moving through space.

A lot of Zomoridinia’s works are derived from her past experiences working with and documenting the pieces created by the art collective Open Five, a group of environmental artists based in Iran traveling between different cities and art festivals.

When asked about her experience working with the Open Five collective, Zomorodinia reflects on the different types and levels of accessibility offered by both Iran and the United States. Open Five being a traveling group, they would often spontaneously pull off to the side of the road when driving and venture off into whichever spot of land caught their eye to use as the setting for a project. Currently in residency at The Headlands Center for the Arts, which is nested upon federal land and highly protected by preservation laws, this difference in approaches to one’s interaction with natural land provoked Zomorodinia to contemplate the difference between personal freedom, as offered by the United States, and freedom of access to land, as offered by Iran, poking into the debate of public versus private. As her awareness about environmental impact grew, Zomorodinia began to wonder about the long-term implications of the art on the natural landscape, asking “are you an environmental artist when destroying nature?”

In response to this question, Zomorodinia began to turn towards video in an effort to be less harmful to nature. Using the landscape as her studio, Zomorodinia eventually built off the idea of the human element in photography to experiment with performance and projection mapping. Never formally taught, Zomorodinia learned simply through the practice of doing.

One of her more recent works include Colonial Walks, an ongoing two-year long project, uses various mapping technologies to create wildly intersecting laser cut and 3D printed sculptures of the spaces she has occupied. Part of the artist’s daily routine includes a walk in nature, which she considers as a spiritual experience. This reminded the artist of the Muslim tradition to make a pilgrimage (Hajj) to the Ka’ba in Mecca and walk around it seven times. After making this connection, the artist went on to consider what it means to reveal oneself to nature and vice versa.

While making this series, there was one, main thing on the artist’s mind – the idea of a house, of a home. As an immigrant coming to a new country, she was largely concerned with making a better and a new life for herself. So, she made her own colony, she made herself a house out of her walks. Zomorodinia questions ownership of land through art making by creating abstracted imaginary spaces that could potentially sell on the market for future ownership. With the aid of such technologies as projection mapping, Zomorodinia offers a trip to impossible landscapes.

These pieces suspend places in created spaces. They allow for the change of existence both with and without light. They are tangible, sellable objects born out of experience – they have been made visible from something as invisible as time.

Another recent work by Zomorodinia is Decolonial Atlas, a recent innovation built off the Colonial Walks series. This series allows for viewers to interact with flags of imaginary places to reclaim an area of space and land for themselves – that is, until it is eventually reclaimed by someone else.

This newer series asks “what is a place?” Through audience participation during the performance, viewers were able to claim Zomorodinia’s imagined places through their own experience of simply living. Zomorodinia wanted to make her own atlas, to make a space solely for her personal use – a map of one’s own. The role of the map here is to analyze how boundaries between city, state, and country limits are made. How is this power of definition between ownerships of land determined and applied? Money, wealth and power play strong roles in establishing such geographic boundaries. Here, Zomorodinia is utilizing the power of technology, and her phone, to make her own geographies.

Spotlight on Minoosh Zomorodinia

By Jawad Izzo, 2018

Since arriving in the United States in 2009, Minoosh Zomorodinia’s search for a safe destination has only further accelerated, both in urgency and expression of form. After speaking to the IC3 Artist-in-Residence, it becomes very clear that her life in Iran leading up to the present was just as critical to this search and, by extension, the art currently being exhibited at the Islamic Cultural Center of North America (ICCNC). For Minoosh, her path has not been entirely straightforward, and how could it be(?), given the political vagaries of the Iranian-American relationship, the practical challenges it introduces, and the constant re-acclimating to spaces, both physical and spiritual, imposed by a life spent in artistic transit.

Minoosh hints at the kind of upbringing that left an indelible impression on her work. She mentions going to a religiously conservative elementary school, becoming exposed to an austere, yet passionate, religiosity at an early age. She mentions her parents’ insistence on environmental conservation and respect for the natural habitat. These experiences, inter alia, were the seeds that grew into her early involvement with the Open Five Group (Panje-Baz), an environmental artist collective at the Jehad Daneshgahi School in Tehran. After participating in 20 different environmental art festivals in Iran, the collaborative effect resulted in a renewed focus on nature, using land and its features as a medium for self-expression and exploring its navigational signs.

Minoosh quickly landed her first show in the United States in February 2010 at the Open Shutter Gallery in Durango, CO, where, as “the ambassador of the movement” in the US, she introduced the Open Five collective and its works of nature to a new audience. The exhibit marked a shift toward multimedia and performance, materializing in an MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute. There, Minoosh found herself more in front of the camera, exploring “intuitive performances” of the body, involving physical repetitions and ritual. She says of the experience: “Part of it was self investigation that was helpful for me, searching to find the right platform…a safe platform,” hinting at her evolution currently on display at the ICCNC, with its central theme of sanctuary. But by this time, the constitutional themes of her artistic output were more apparent: the repetition of spiritual practice, the regimen of movement and order, nature as an indicator of safety and its function as terra firma, not only for the body, but for the spiritual self.

I inquire about this “self,” its constancy, and its transformation through creativity. Minoosh refers to the self as a process of negotiation, without a clear-cut answer as to its true identity. She rhetorically asks: “Is it the soul? Is it the ego?” But one thing is clear:

“The self definitely changes when you are involved in the creative process, and sometimes it’s very heartbreaking, because being an artist involves creating a personality which becomes part of your life. It is your life. If you’re a doctor, you go to work and return home to your normal life. But being an artist is always with you and you cannot stop being an artist. Being an artist, it reflects on the style of your work and (the state of) your brain.”

Even a cursory glance at Minoosh’s work strongly indicates the difficulty in compartmentalizing this (artistic) self, with its flux of materials, natural and synthetic; Dirt, metal, flesh, cloth, stillness, movement, each and all the technology of the self and the indispensible wherewithal of the earth itself.

The most immediate expression of Minoosh’s self is what appears as the features of a practicing Muslim. “It’s the first expression of whoever looks at me.” She is quick to point out, however, how this distinction can sometimes be a distraction as much as an insightful indicator. Since Trump’s election, she has received more invitations by artists to collaborate, but is suspicious, “because I want people to see my art and not my appearance. I’m not making promotional or commercial art.” This has caused her to scale back on the use of the body and its coverings, increasingly charged and politically inflected by the times. Instead, Minoosh has taken the theme to deeper, more latent depths. In her current exhibit, “Imagining Sanctuary,” she traverses-quite literally-new landscapes with the theme of sanctuary, with special ritual walking tours around Lake Merritt, among other paths, along which fellow pilgrims are encouraged to contemplate the natural habitat and the feeling it elicits. She comments on the notion of home and the safety and comfort provided by these landscapes:

“In America, you can find gas stations on every corner, and in Iran it’s mosques…creating home. After learning about ‘sanctuary cities’ after the election, I had a desire to connect these concepts. Sanctuary is a place for refugees and a sacred space. Naturalism is crucial to being safe, and water is one the symbols of safety.”

Rarely has the space of an exhibit been so crucial to Minoosh’s show. She says of her residency at the ICCNC, “I really love the building and am fascinated by it. This is not an art space and the people coming are mostly practicing Muslims, (presenting) different audience opportunities.” For the first time, Minoosh is seeing “how Muslims, my community, view my work, which is a different response. They might not necessarily understand art.” The overlap of events at ICCNC presents an additional novel component, with visitors prompting compelling conversations, connections to spirituality, and relations to their experiences. Recently, Dr. Abdolkarim Soroush stopped by the exhibit after delivering a lecture at the Center. His response: “mutahayyar”: astonished.

Minoosh Zomorodinia’s solo show, “Imagining Sanctuary,” will hold its closing reception on Saturday, April 21, at ICCNC.

A New Type of Flâneur Strolls in Search of Humanity

By Erin Langner, March 7 2018

TACOMA, Wash. — What does it mean to be a flâneur — to stroll about, consciously observing by some definitions, merely loafing by others — in the current political moment? The “strolling by” definition lacks a sense of urgency. In this moment, can anyone, other than the most privileged, live at enough of a distance from pressing issues, like human rights violations, discrimination, and the planet’s health, to saunter?

I found myself considering a new type of flâneur while surrounded by the work of Bay Area artist Minoosh Zomorodinia. Strolling resides at the heart of the installations, sculptures, video, and digital prints that comprise her Colonial Walk, a small show presented by Feast Arts Center in Tacoma. While on residencies in California’s Marin Headlands and Lyme, Connecticut, Zomorodinia took regular walks and filmed them. She then deconstructed these recordings into fragmentary images — a streambed, a patch of dirt, rock walls — and reassembled them into photographs and digital projections. Guest curator Thea Quiray Tagle explains that for Zomorodinia, who was born in Iran, these “psychogeographic” pieces raise questions of how immigrants find a sense of home.

In “Land Mark” (2018), the show’s largest piece, Zomorodinia projects a gridded montage of landscape surfaces across a gallery wall, while a jagged floor sculpture made of matte paper and wire fills the room’s center. The sculpture’s walls evoke both a children’s play fort and a discarded mass of paper; the experience of standing inside them, as the projections covered both the walls and my own skin, was mystifying. The landscape elements I could identify felt familiar; having once visited the Marin Headlands, it seemed like I should be able to discern the images’ sources. Yet, they never offered the relief of constructing a graspable place, instead leaving me with a sense of unsettlement and unknowingness. I wanted to figure out which segments belonged to which walk and hoped the artist might appear as a guide in some form but only found myself stranded with the impossible task of orienting myself within the strange place she constructed.

Zomorodinia’s physical absence in Colonial Walk is a strong statement. The 19th-century Parisian flâneur voluntarily removed himself from the world in the interest of engaging with it anew. By contrast, Zomorodinia’s person-less wanderings prompt a sense of yearning for connection and human contact within the places they portray. “Throughout Minoosh’s practice, you see her tackling questions of space: how we move through space, how we make our mark on built and natural environments that can be extremely hostile,” curator Tagle explains. The sites of the artist’s residencies are known for their physical hostilities: gusty Pacific winds fill the Marin Headlands and the ticks that cause Lyme disease are the namesake of the Connecticut town.

These questions, especially in light of ideas of immigration in Zomorodinia’s work, make for ripe metaphors in a time of refugee bans and deportation raids by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement. One can imagine how hostile environments would abound for immigrants who thought they had found a sense of home in the United States. Even those who have not been physically detained may experience a sense of involuntary emotional removal from a place they thought they knew — a place they thought they belonged to.

The wall installation “Missile Map 1 and 2” (2018) at first seems subtle and quiet in comparison to the rest of Colonial Walk. The set of delicate wire and paper sculptures showers one wall of the gallery with silent, frozen explosions that are similar in size and shape to an outstretched human hand. Witnessing these flailing bursts, I came back to the idea of a new, more relevant flâneur. I could now see this figure as someone who walks aimlessly in a way that brings attention to the way a place can suddenly become unrecognizable — one where hands open but meet nothing but air, one in need of an urgent change in order to recover a sense of humanity.

Minoosh Zomorodinia: Colonial Walk continues at the Feast Arts Center (1402 S 11th St, Tacoma, Wash.) through March 11.

“I found myself considering a new type of flâneur while surrounded by the work of Bay Area artist Minoosh Zomorodinia.” Erin Langner

‘Colonial Walk’ overwhelms

By Alec Clayton, Weekley Volcano 2018

Much as been written online and elsewhere about Minoosh Zomorodinia’s “Colonial Walk,” an art installation and gallery exhibition, parts of which are on display at Feast Arts Center. According to the gallery website, it is a project in process that investigates the relationship between the self and the natural environment, explaining: “Meditating on the ways immigrants can or cannot make home in the United States, Zomorodinia takes dérives (or psychogeographic walks) through nature, mapping her routes with geographical information systems (GIS) software and other programs. The videos taken along her routes are then reconstructed into abstract pathways, and are projected onto larger sculptural forms.”

The dominant feature of the installation is a sculpture in paper, tape and wire of a geologic formation that stands about eight feet tall in the center of the room and upon which is projected images of rock formations. It is called “Land Mark.” The structure is circular and open on one side so visitors can view it from all sides, inside and out. The projected images land on the sculpture and on the wall behind it – actually the front wall of the gallery, with windows covered. The projected image permeates the entire room with muted gray, pink and violet sunset colors and creates optical movement such as in moiré patterns. If you watch closely while someone steps inside this sculpture, you can see the walls close in on them. Whether this is an optical illusion or actual movement is debatable, but since it is made of light materials that hang from the ceiling, it is likely that the wind created by the entering body makes the walls move.